Earlier this year, Gingko Press published Emigre Fonts: Type Specimens 1986-2016, a comprehensive collection of Emigre’s distinctive print samplers. A couple years previous, I went through my personal collection of their specimens dating back to the early 1990s and wrote this appreciation for a project that wasn’t realized. However, on the (late) occasion of Emigre’s book, here’s the essay.

When Rudy VanderLans announced that issue 69 would be the final publication of Emigre magazine, he emphasized—via a “reminder” from partner Zuzana Licko—that it wasn’t the end of the company. Considering the magazine’s primary role in determining Emigre’s identity, and that the journal was its namesake, the notice was necessitous. The foundry that had become the core business would continue developing and vending type.

In addition and importantly, the specimens that promoted their typographic works would continue to be produced. VanderLans had separately declared a commitment to continue these print pieces. The pledge placed Emigre in a distinct minority. We’re in a time that has seen a marked decrease—if not total abandonment—of foundries issuing physical type catalogs. Whether it was a decision based in pragmatic marketing or a nostalgic nod to the unended print, VanderLans’ avowal was welcome among aficionados of everything Emigre. The magazine was an acceptable but tough loss. Having to also bid farewell to the catalogs could have been devastating.

While Emigre magazine was a fundament in its firmament of products, it was always only one aspect of a constellation of printed works that grew up around it and the foundry. By VanderLans’ estimate, the company has generated close to 200 printed artifacts, comprising catalogs, specimens, posters, brochures, postcards, pamphlets, and other printed ephemera published since 1984. All converged in the magazine and spun off from it.

Foremost amongst those ancillary works were the specimens that introduced individual or a selection of faces, and the annual inventory of the Emigre library. In the magazine’s heyday, the boundaries between it and the specimens blurred. For many designers and some critics, Emigre magazine was little more than a glorified type catalog. Curiously, and revealingly, the distinctive critical content is downplayed, if not dismissed. The pioneering type design and marketing originalities are highlighted. Zuzana Licko’s typographic innovations have been evidently easier for the design field to assimilate than the ideas set in her landmark faces.

The appraisal of Emigre magazine as elaborate sales brochure denigrates both the journal and the full-fledged specimens. Emigre absolutely made, and continues to make, glorified type catalogs—but they are the catalogs.

Emigre’s type specimens are the intersection of its two signal accomplishments, the magazine and type design. They are also the most representative artifacts of the partnership of Licko and VanderLans. The reputations of their other products understandably overshadow the catalogs. While the magazine and type have received considerable attention and documentation—most recently in the Emigre no. 70 anthology—the specimens go largely unnoted.

Both for their connection to and fusion of Emigre’s more celebrated work, and as artifacts in their own right, the type specimens are worthy of separate attention. All the aspects of Emigre’s contributions to contemporary design are present in form and content. If, as Rudy VanderLans regarded them, issues of the magazine are considered graphic “albums,” the specimens are the “EP’s” and “singles.”

Emigre’s specimens are notable for the negotiation of practical considerations and creative idealism—the essence of all graphic design. They demonstrate an adept dovetailing of these concerns, crafting a format that stimulates desire then provides an efficient vehicle for satisfying it. A balance is struck between providing an enthusing context for the type while not overwhelming it. Though far from “neutral,” the framework is evocative and clear.

This framework has become more involved than embellishing the traditional catalog display. A rethinking of purpose and presentation is evident across the history of the pieces. Emigre’s specimens advance upon earlier examples of the form that utilized it to advance a wider conceptual agenda on how typography is defined and practiced.

A precursor is William Addison Dwiggins’ specimens for his new type designs. His were more realized, progressive publications centered on type display. A simple necessity was embraced as opportunities to explicitly express his typographic philosophy.

Dwiggins’ “Emblems and Elektra” specimen eschewed the rote alphabetic exercise to put forth a manifesto. “How is one to evaluate and assess a type face in terms of esthetic design? Why do the pace-makers in the art of printing rave over a specific face of type? What do they see in it? Why is it so superlatively pleasant in their eyes? Good design is always practical design. And what we see in a good type design is, partly, its excellent practical fitness to perform its work.”

Of course, that final statement is purely subjective. But as is often the case, the distinction of the type design supplies affirmation for his rhetorical position. Plus, you get a measured dose of Dwiggins’ delightfully idiosyncratic abstract illustrations.

Along with spurring a surge in digital type design, Emigre’s catalogs sparked a spate of inventive promos from a variety of short-lived and established foundries. Simply having the specimens was a practical necessity that isn’t attributable to Emigre. But the venturesome contexts adopted by many of the other foundries owe a debt to Emigre’s examples.

Often, the specimens were the most—sometimes only—interesting aspect of these other type designers’ efforts. As abstract works, separated from their sales imperative, they were engaging artifacts, parading wild, unfettered graphic novelties riffing off the theme of character sets. As proffers of usable type, they were far less viable. Simply put, I’d rarely imagine ever using faces from these specimens. But as elements in an “artist’s book” of Roman characters, they were engaging marks.

That the faces were disposable didn’t lessen the charm of the specimens, which could get baroque in concept and hyperactive in the number and variations on a theme. Another intriguing exponent of the surge in specimens was that they provided scarce examples of graphic design by individuals known foremost as type designers. Jonathan Hoefler’s Muse publication lasted the one issue but was succeeded by a few catalogs that shared the same delightful classicist sensibility. Much as I admire his typefaces, I’d put money down for more Hoefler print objects.

The earliest Emigre specimen I own, “Signs of Type,” is similarly unique for its rare “Design: Zuzana Licko” credit. Absent the notice, the piece might easily be attributed to her partner in its presentation of her low-rez faces illustrated with bit-mapped scans. With all respect to Rudy’s work, I’d fantasize at times that on a lark, Zuzana might take on the layout of one my articles and afford me a singular design triumph.

The overall design sensibility of Emigre specimens naturally moved in parallel with the flagship magazine. Roughly, specimen history can be divided into the pre- and post-4-color eras. Pre-color, the specimens proffer VanderLans’ distinct formal sensibility but are straightforward in text and concept. The phrases set in the faces are descriptive of the type’s features and formal rationales. Or, as with Dwiggins, propound terse typographic manifestos: e.g. “Typefaces are not intrinsically legible; rather it is the reader’s familiarity with typefaces that accounts for their legibility. Studies have shown that readers read best what they read most.”

With the advent of full color publication—the time leading up to and after the end of Emigre magazine—the specimens bloom as deeper, broader artifacts in their own right. A preservation principle seems at work. The energy of the magazine couldn’t be destroyed, only channeled and adapted into another form. One of these alternate outlets was VanderLans’ book projects— Supermarket, the Palm Desert/Cucamonga/Joshua Tree music trilogy. And the specimens also received an additional infusion of vitality.

Specimens became small journals in their own right, offering broader speculations and investigations of type design. Short accounts of a face’s origins and the designer’s intentions regularly appear and expand. Experts such as John Downer provide extended essays on topics related to typographic revivals.

The text examples become extended haikus or proffer full-on stories. Writer David Barringer was commissioned to bring his fluent prose to the two volume “Little Book of Love Letters.” Other republished texts feature early-20th century writers on subjects like the geography of the U.S. southwest (a VanderLans obsession).

Other specimens give the type designers the opportunity to frame their creations in artist-book quality promotions. The late Frank Heine crafted two amazing booklets for his Tribute and Dalliance faces. Mark Andresen wrote and illustrated a VouDou tale for his NotCaslon booklet. Mr. Keedy generates a visual/textual polemic for Keedy. Elliott Earls does Elliott Earls. VanderLans himself imagines eccentric and elaborate historical markers for the Historia specimen.

The ultimate and ongoing charm of the pieces transcends their status as product catalogs. However attractively designed any specimen may be, it is as disposable as any graphic design artifact, if not more so. That the specimens’ primary type product is essentially unchanging presents a significant design challenge. Change is mostly through accretion: the addition of new faces to the library.

In broader terms, a common charge against graphic design as a discipline is the unapologetic disposability of its product. The overwhelming majority of graphically designed artifacts are properly characterized as ephemera. What then the products for a graphic design audience? Is the factor doubled? VanderLans’ fancy flights confront these realities and serve a very pragmatic purpose: how to make the same collection of forms fresh.

The particular genius of these works is their beautiful functionality: an equal balance of abstract aesthetic qualities and clarity of use. The feature in the specimens that best expresses this balance was the now discontinued order form. Their layouts were also divided across the introduction of process color. Within these diversities, they’ve remained fairly consistent: an incidence of an inability to improve upon perfection.

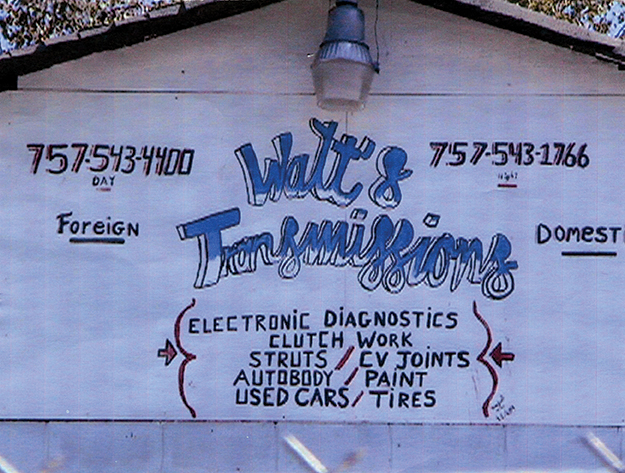

The forms are the most succinct expression of VanderLans’ design approach (his “inner classicist” in Rick Poynor’s description)—an articulate and resonantly apparent structure. As formal compositions, the order forms residing somewhere between El Lissitzky’s “prouns” and Sol LeWitt. Pre-process, the layouts were all right-angular, sectioned by thick rules that strategically extended beyond the form’s basic framework. With the introduction of color, circles came into play, accenting in hues and shapes. Actually writing on the forms didn’t ruin the effect. Rather, it became a lively, improvised vernacular accentuation.

Often, the underlying structure of VanderLans’ layouts are visible and made decorative graphic elements in its own right. (See Emigre #40, The Info Perplex issue for his most elaborate expression). This strategy has tangential relation to designs that display a visible grid, as can be seen in a number of classic Josef Müller-Brockmann posters. VanderLans’ structures, however, are more flexible and colorful. Their agile geometries are efficient to their task of segmenting and structuring space.

If enthusing over an order form as a counterpart to signature works by renowned artists isn’t grandiose enough, I’ll take a step further. As previously mentioned, many of the booklets stand among the finest artist books of any era. The Hypnopædia specimen, for one, is a marvel of pattern and color that rivals many painters’ output—not to mention its status as a triggering expression in the “rational/decriminalized ornamentation” movement now in full flower.

More than this, these specimens provide one of the best examples of graphic design demonstrating content in its own right. It’s a near universal tenet that graphic design is an applied activity, possessing no substance upon its own. But when considering these catalogs, they can be “read” the same way that abstract painting are. A color field painting by Mark Rothko is “about” color, physically about paint. These specimens are about character forms, physically about type. The specimens transcend the mundanity of words to express ideas of the representation of language. We can contemplate the letter as we might upon the hue of blue.

It is a charge, a challenge, I regularly place upon my students, and ultimately upon all graphic designers. Is this discipline of graphic design worthy of contemplation on its own terms? Might you pick up any graphic design artifact and enjoy it for the pure joy of its unique status that straddles and fuses form and function? Can you pick up and delight in a type specimen as you would a painter’s (or sculptor, or photographer, or what have you) monograph? Not seeking professional “inspiration” but sensual indulgence?

Graphic design artifacts are like nothing that came before them. Their motives and intentions are unlike any creative form now or since. And this stature is best represented in forms like type specimens. They speak volumes of potential, in the works they will conjure into being, and what they suggest for how we regard our past and current print culture.

A thorough documentation of the Emigre’s specimens is a valuable undertaking. Like the entire Emigre enterprise, the boundary was sometimes crossed to encompass booklets for its nascent music label, and some non-paginated pieces (though excluding posters). I’ve focused on the type aspect of these pieces, though most may be rightly considered catalogs for the entire Emigre product line. Whatever you want to call them, enjoy.